It may be the most toxic word in American religion — evangelical. It’s almost used as an epithet now.

I am fascinated by that, by the way, because I grew up evangelical — literally as evangelical as you can get, in a nearly 100% White Southern Baptist Church in a small town in Southern Illinois in the 1990s. That’s the epitome of evangelical.

Yet, I cannot, for the life of me, remember a single instance when that word was mentioned from the pulpit or in the pews or the hallways of that church. In fact, I didn’t really become aware of it until I went to college. Then, it was actually a big topic of debate at Greenville (which is aligned with the Free Methodist Church). Some folks thought we should lean into the label — others thought it wasn’t a good idea.

I didn’t care either way because I didn’t really know what the term meant. Funny to look back on my total ignorance of the word “evangelical” then, as I now have actually debated other folks on what the word means.

Here’s the purpose of this post: figuring out just how many Americans have shed that label in the last several years. The CES asks every single respondent, do you consider yourself a born-again or evangelical Christian or not? Only two response options — yes and no. It’s about as simple and straightforward as you can get. So, let’s get to it.

Your tax-deductible gift helps our journalists report the truth and hold Christian leaders and organizations accountable. Give a gift of $30 or more to The Roys Report this month, and you will receive a copy of “Hurt and Healed by the Church” by Ryan George. To donate, haga clic aquí.

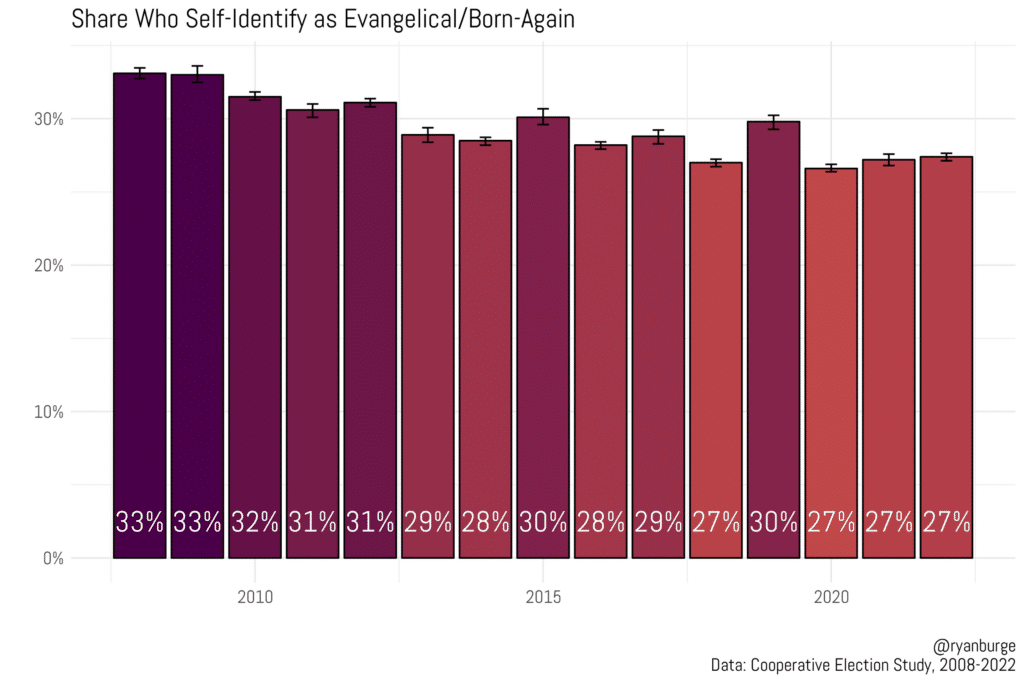

In 2008, a full third of the sample self-identified as evangelical. But in the next five years or so, there was a clear decline. By 2013, that share had likely dropped below 30%. In the last three years of the survey, the share of American adults who self-identify with the evangelical label is consistently around 27%.

That’s a full six point decline in the evangelical label. For perspective, Jews, Latter-day Saints, Hindus, Buddhists and Muslims together are probably right about 6% of the population. Six percent is a lot.

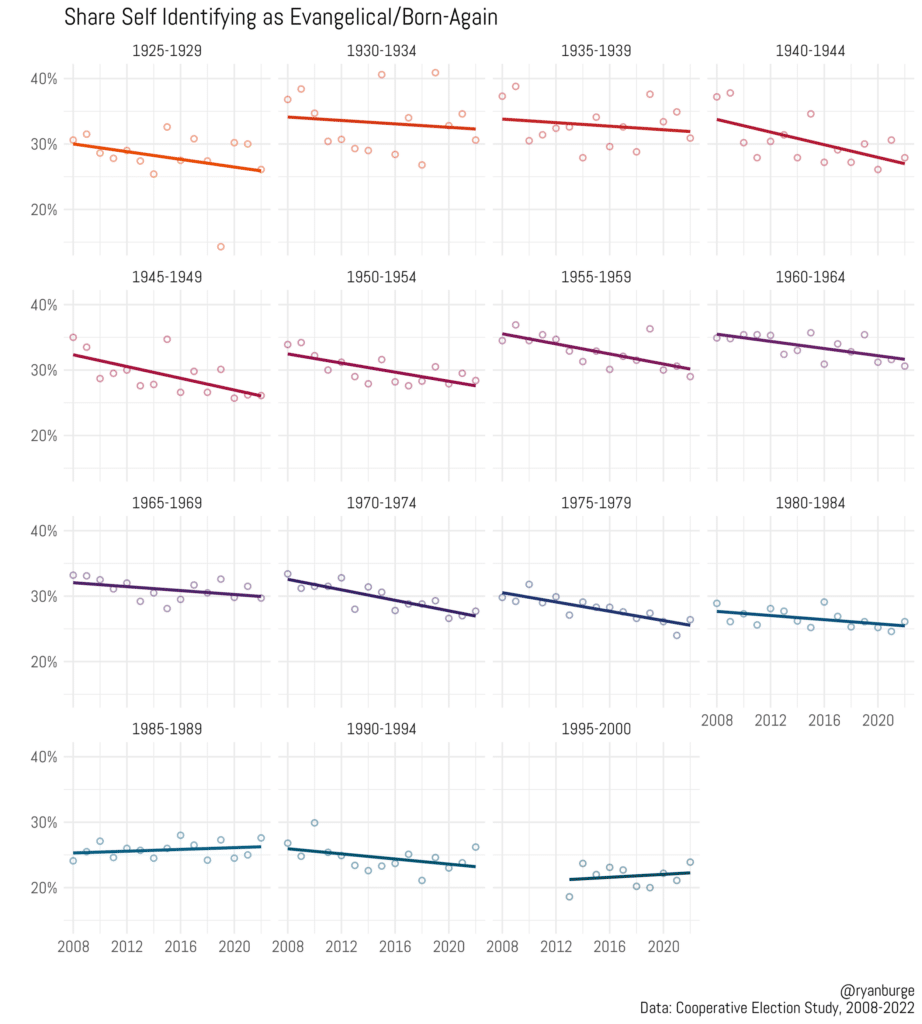

But, obviously that decline is not happening evenly across every demographic group in the United States. Some are probably walking away from the label faster than others, right? Let’s find out. I am starting with age now. These are five year birth cohorts, which is my preferred way of gauging the impact of age on some other variable.

That’s a lot of lines that are pointing in the downward direction. And what is really striking to me is that it’s happening across all kinds of birth cohorts, young and old. Now, it’s clear that the pitch of those lines is not all the same. For instance, those lines in the second row (1945-1964) are particularly steep. That means that the term evangelical has become especially unattractive to folks who either retired or are getting very close to it.

It’s noteworthy that the last two rows of birth cohorts don’t show a decline that is nearly that aggressive. For instance, the 1980s cohorts are pretty uneventful compared to the older generations. In fact, among those born in the late 1980s, the share who self-identify as evangelical has actually risen very slightly since 2008. Also, check out the youngest cohort — those born between 1995 and 2000. That line is pretty much flat, too.

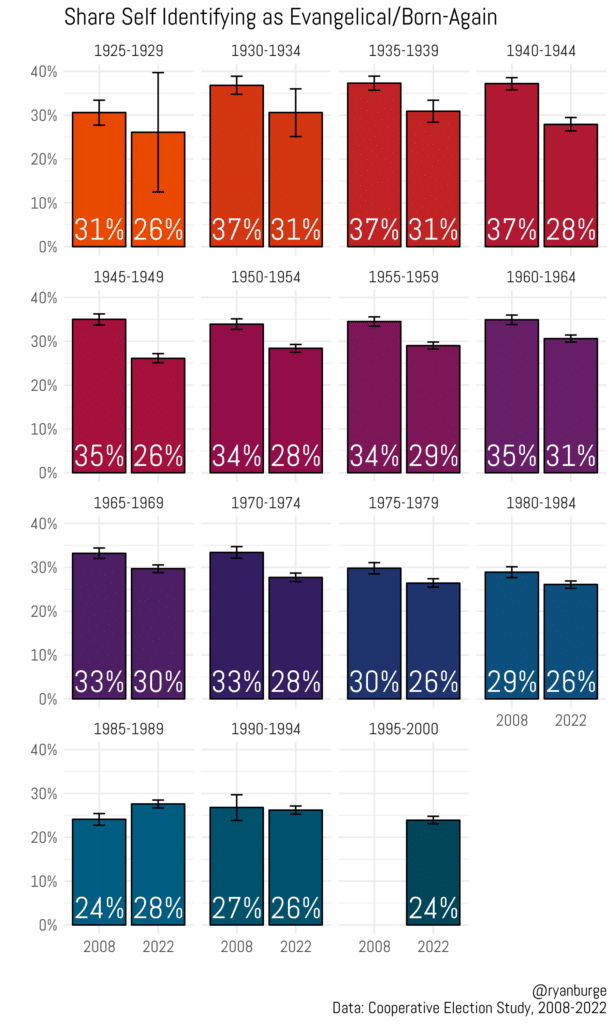

I wanted to simplify that last graph by just comparing the evangelical share in 2008 with that same share in 2022. Again, this is broken into birth cohorts and the capped lines represent 84% confidence intervals to give us a sense of when the differences are statistically significant.

Look at those born in the 1940s — that really jumps off the page. The share who identify as evangelical has dropped by nearly 10 percentage points between 2008 and 2022. I just can say unequivocally that those are the biggest drops in this entire graph. That’s pretty shocking to me.

If you look at younger cohorts there is a decline, but I think it’s accurate to call that a pretty modest dip. For instance, it’s just three points among those born in the late 1960s. It’s the same drop among those born in the early 1980s. But look at that bottom row. The late 1980s cohort has seen an increase in evangelicals (from 24% to 28%) and the late 1990s cohort is unchanged. So, the drop among evangelicals in the entire sample is likely being driven by older Americans, not younger ones.

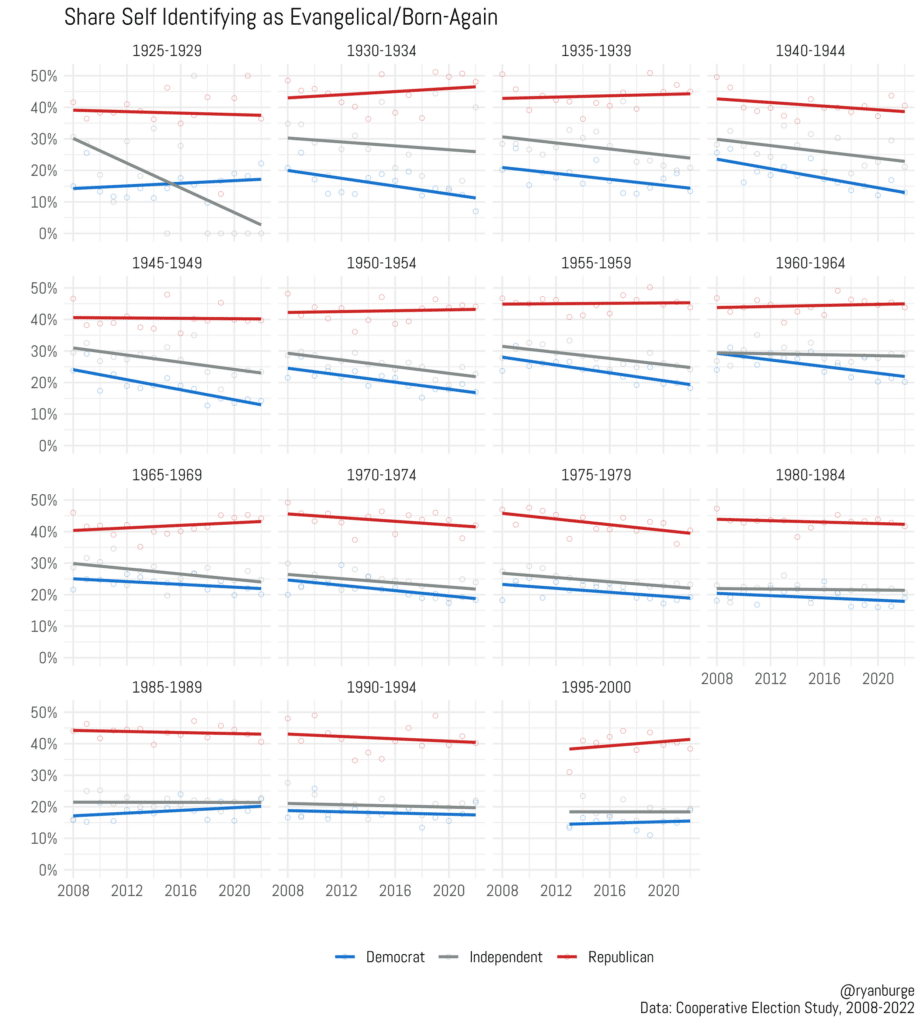

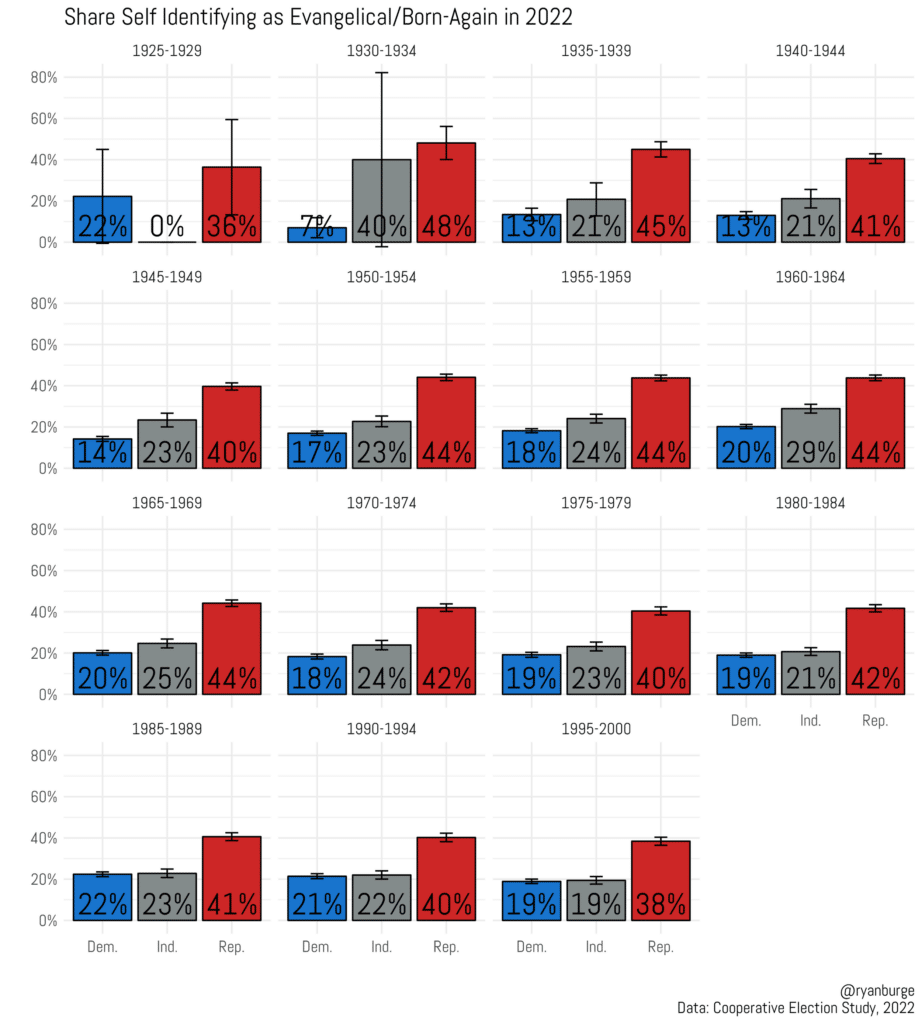

But, of course, the elephant in the room in any discussion about evangelicals comes down to politics. There’s no doubt that the word evangelical has a significant political component to it now compared to 20 years ago. So, let’s try that out. These are birth cohorts that are further broken down into Democrats, independents and Republicans.

OK, let’s get this out of the way. Republicans are more likely to self-identify as evangelical compared to independents or Democrats. I know that we are all shocked by this revelation. But the red lines are pretty instructive. Trace them across the top two rows — they are perfectly straight. That means that older Republicans are not shedding the evangelical label. The bottom two rows have a bit of mixed evidence, though. There are clear declines among Republicans born in the 1970s, but some other cohorts are pretty straight across.

How about the blue lines? Yeah, those are almost always pointing downward. Remember how the big dips in evangelical identity were concentrated among older Americans. Let’s get even more specific — it’s older Democrats that are walking away from the evangelical label. And they aren’t small declines, either.

For instance, look at the early 1940s cohort. About 25% of Democrats were evangelicals in 2008. That’s dropped in half now to just 13%. The next cohort over reported a drop that was nearly 10 points, too. This is the norm, in fact, for older Democrats — a drop of 8-12 points in identifying as evangelical. That’s really significant and tells a pretty compelling story of how the politicization of the evangelical label has turned off a lot of baby boomers.

But I wanted to make it plain just how big the partisan divides are when it comes to the evangelical label by graphing the share who are evangelical in 2022 based on political identification for every cohort.

The 1945-1949 cohort just jumps out to me. A Republican in this age group is nearly three times more likely to identify as an evangelical compared to a Democrat (40% vs 14%). But the gap in the cohorts born in the 1950s is 27 points and 26 points, respectively. In fact, they’re the oldest cohorts where Democrats are the least likely to identify as evangelical, not the youngest one.

In the youngest cohorts, the gap actually narrows just a bit. For instance, among those born in 1985-1989, 22% of Democrats are evangelicals compared to 41% of Republicans. That same basic gulf is apparent in the two youngest cohorts, as well. But what could be driving this? I think one possible answer is a pretty simple one: race. Younger cohorts are way more racially diverse than older generations.

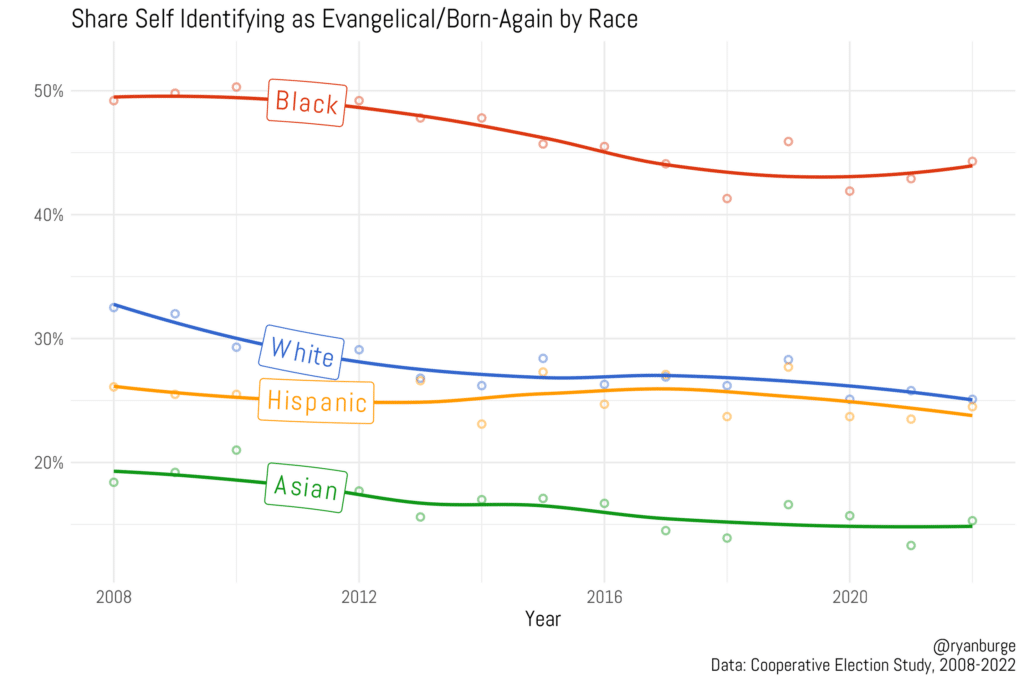

This may be the most myth-busting result from this entire analysis: the racial group that is the most likely to self-identify as evangelical/born-again is African Americans. And it’s not even close. In 2008, about half of Black respondents said that they were evangelicals. It’s dropped a bit to about 45% in 2022. But that share is still much higher than any other group.

When folks talk about evangelicals, it’s almost always implied that it’s White evangelicals. But in 2008, only a third of White respondents said that they were evangelical. It’s dropped to just 25% in the most recent sample. Think about that: 45% of Black folks are evangelicals, compared to only 25% of White respondents.

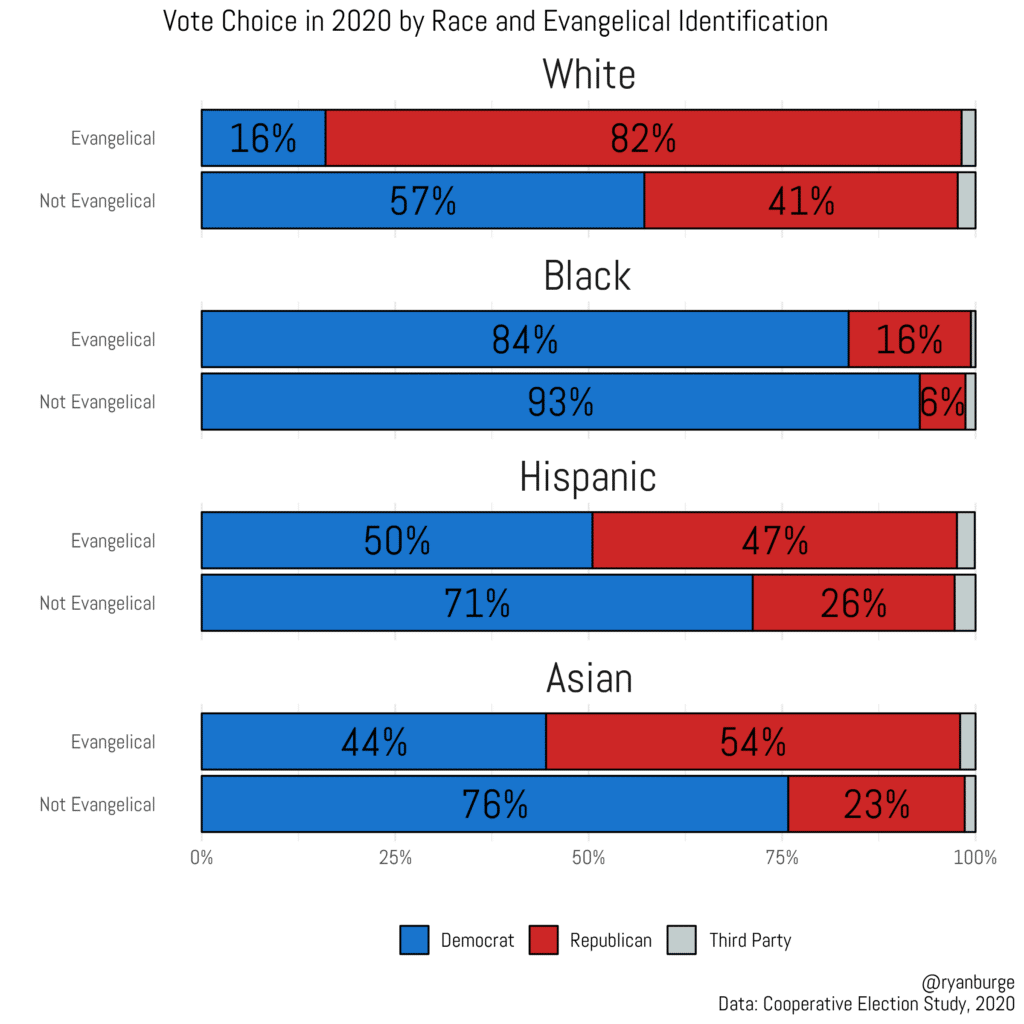

I think one of the biggest reasons that there isn’t more discourse about Black evangelicals is because that label just doesn’t seem to matter a whole lot when they go to the ballot box. This is vote choice in 2020 among racial groups divided into evangelical and nonevangelical categories.

It should come as no big revelation that White evangelicals really liked Donald Trump. He got 82% of their votes. Among nonevangelical whites, Biden did much better at 57%, while Trump only got 41%. That’s a 41-point gap based on evangelical status.

For Black respondents, the difference in vote choice among evangelical and nonevangelical is fairly small. Trump only got 6% of Black respondents who did not identify as evangelical. He got 16% of the Black evangelical vote. Ten points is not nothing, but it’s most certainly not 41 points.

I do want to point out that the evangelical vote gap is large for Hispanics and especially Asians. Among Hispanic evangelicals, the vote was almost evenly split — 50% for Biden and 47% for Trump. For nonevangelical Hispanics, Biden dominated (71% vs 26%). For Asians, the gap was even larger. Trump got a majority of Asian evangelicals (54%). He only earned 23% of nonevangelical Asian voters.

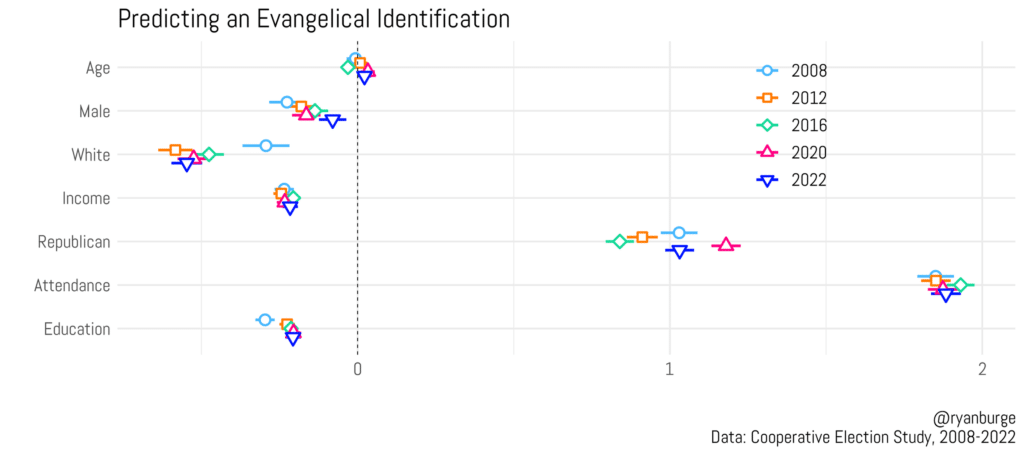

I wanted to end this post with a regression analysis. It’s just the way that social science holds some variable constant while looking for the impact of other factors. I included all the usual suspects here: age, gender, race, income, education, Republican affiliation and weekly church attendance. I wanted to see which were the most predictive of someone self-identifying as evangelical.

It’s easy to interpret this graph. Anything to the right of zero means that the variable predicts a greater likelihood of being an evangelical. Anything to the left predicts a lower likelihood. However, if the estimate overlaps with zero, there’s no relationship between the two variables. I estimated this model for five different years of the CES to see if things have changed over time.

I can tell you this: There are a bunch of factors that make someone less likely to be an evangelical. Being male, being White, having higher household income, and higher education are all predictive of being less apt to identify as an evangelical. The age variable is clearly a mixed bag — not predictive either way.

There are two variables that make someone more likely to be an evangelical, and they should come as no surprise: weekly religious attendance and identifying as a Republican. Now, in this model, weekly attendance is by far the strongest predictor of self-identifying as evangelical. But it’s interesting to me that even when you throw in a religious variable, there’s still a strong positive relationship between aligning with the GOP and being an evangelical.

It’s not just religious activity that is driving people toward evangelicalism. That’s a clear empirical finding from these results. Evangelicalism has become an amalgam of both religious and political factors that are really hard to untangle.

I really like Ruth Braunstein’s thoughts on this subject in an article she wrote for the Guardian last year. It was entitled, “The backlash against rightwing evangelicals is reshaping American politics and faith.” Her thesis was simple, yet profound: Evangelicalism has essentially purified itself in the last several years. It’s made some people even more committed to the religious movement and its cause. It’s also pushed a lot of people out.

I always think of Moses and the parting of the Red Sea. He lowered his staff and the sea retreated to the right and to the left. Donald Trump has been the Red Sea movement for the evangelical movement. He’s forced people to pick a side in a way that previous presidents didn’t. I don’t think anyone would call George W. Bush the Great Divider.

Is a smaller, yet more faithful movement a laudable goal? That’s for other people to decide. But it does seem like that’s the choice that the evangelical movement has made in the last several years.

The views expressed in this commentary, which was originally published at Ryan Burge’s “Graphs About Religion”, no reflejan necesariamente los de The Roys Report.

Ryan Burge es profesor asistente de ciencias políticas en la Universidad del Este de Illinois, pastor de la Iglesia Bautista Estadounidense y autor de “Los nones: de dónde vienen, quiénes son y hacia dónde van.”

Ryan Burge es profesor asistente de ciencias políticas en la Universidad del Este de Illinois, pastor de la Iglesia Bautista Estadounidense y autor de “Los nones: de dónde vienen, quiénes son y hacia dónde van.”

14 Respuestas

How do you define “born again?” The Ancient Churches have taught that being “born again” is when you are baptized. Hence, baptized Eastern Orthodox (such as myself), Armenians, Copts, Roman Catholics and others are “born again.” Being “born again” is not when someone makes a mental assent to Christian doctrine. Take a look at the “Born Again” Wikipedia page for the variety of Protestant positions.

The survey is counting only Protestants that consider themselves, by their definition, to be “born again.” I consider myself to be “born again” but I am not a Protestant. Search “Eastern Orthodox teaching on being born again” and see why we believe what we believe. Please do not go to a Protestant website that attempts to explain what we believe and practice.

As an aside, does anyone have an idea of what word will succeed the word “Evangelical”? The word “church” has been disappearing from the names of individual churches, I assume for marketing reasons, because folks think that non-churchgoing people are put off by church and church people in general. Church names sometimes include the French word “pointe,” which seems like a pointless (!) affectation.

While from a theological standpoint, I am a Black evangelical, I have stopped using the label evangelical. At first, I often laughed at the “isn’t that an oxymoron” type of questions that would follow – as there are quite large numbers of us. If anything, I saw these questions as an entry point to share my faith. However, I realized that it would just further confuse people due to the (embarassingly unBiblical) political alliances and behaviors affiliated with the term.

I now simply say I am a Christian or follower of Christ.

Marín,

I think you nailed a harder to measure aspect of the evangelical label.

Many folks -including myself- would intellectually self-identify as an Evangelical on a survey, maybe in church and perhaps to understanding friends and family.

However, in public discourse, at work, etc, the term carries too much political and social baggage (most of which I don’t carry) as to be a detriment to communication.

It wasn’t always this way. 20 years ago it felt like a more neutral term, but those days are gone. So now I also default to “Christian”. Vague perhaps, but easier to define when the opportunity arises.

Evangelical has had a historic, technical definition. The Bebbington Quadrilateral characterizes this historic, technical definition and the ethos. However, that term has been hijacked by the Christian Nationalists, MAGA-cultists, Trump Kool-Aid Drinkers, and the like. And based upon the behavior of most of them, they are anything but evangelical according to the historic understanding of the term. This is why 81% of “Evangelical” “Christians” supported Trump in 2020 and will like do so again (notwithstanding the new character issues he has had while he was POTUS and afterwards). This is why Evangelical has become a dirty word, and an object of scorn, ridicule, and contempt. And deservedly so.

Mark Noll wrote a book in 1994 called the “The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind”. He recently issued a new edition in 2022 with new material (including the support of Trump, the support for conspiracy theories, the ever-increased anti-intellectualism). The first line of his book (both editions) states, “The scandal of the evangelical mind is there is not much of an evangelical mind.” And that is why most Evangelicals fell for Don the Con.

A positive relationship in a regression analysis does not always mean causality. So for example, being Republican does not cause one to be evangelical (or the inverse being a democrat doesn’t exclude one from being evangelical). I think you would have to show direct evidence for this in the majority of evangelical churches teaching the majority of the time. Usually in cases like this, there is a common factor for both variables shown a positive relationship. Based on Barna studies over the years, there is an obvious decline in core orthodox beliefs and beliefs would explain the common variable.

I don’t doubt there might be perception that Republican has become synonymous with evangelical and maybe that is something to be aware of in a churches’ philosophy of ministry. But we can’t perfectly control perception (although PR might be the cause for the recent negative stigma for the word evangelical) and so the answer has to be a focus on propagating the message of the scripture – persuading/discipling people to biblical beliefs. Division is going to happen as a result of discipleship (the gospel narratives show that and Jesus and Paul alluded to it) and all we can do is continually check our practice to make sure that it is not the cause. This analysis is promising more than it can really deliver to answer this question.

It’s as simple as American Evangelical = Trump cult. It’s absolutely repulsive, and there’s no coming back from that.

That’s a narrative that has been built. It is a perception that was amplified. And there are other problems with evangelicalism that are causing this shift. If it was purely Trump, the data above would have a more dramatic shift around 2016, but there isn’t so you can’t prove that is real across ALL of evangelicalism.

I would question the way the last paragraph talks about a “smaller, yet more faithful movement.”

Could it be that the “evangelical” movement in the U.S. has gotten smaller by being LESS faithful?

Maybe it is those who still follow Jesus but have dropped that label (because of its associations with the heresy of Christian nationalism, lies and conspiracy theories, and fascist-leaning politicians) who are the more faithful ones.

This would be my observation as well, though to be fair, faithful might mean faithful to the label, not necessarily faithful to the gospel.

BINGO! SPOT ON. THE DISGRACE OF THE GOSPEL.

One of my questions is How many of those who abandon the word ‘Evangelical’ still show all of the same characteristics of being an Evangelical?

George,

I would say a fair number, if I was to guess. The problem is the term has been hijacked by all the posers and have sullied the name. Of course it does not help when 81% of Evangelicals supported Trump (and many of those genuflect towards and idolize Trump as their real lord and savior – not some rabbi from Nazareth).

Wow, so 81 percent of Evangelical Christians who voted for Trump are heretics? Maybe we voted for Trump because he is prolife, unlike Biden who advocates for the murder of humans up until the time of birth. It was an easy choice for me. (“Now choose life so that you and your children may live”)

And, yikes, all the nasty, demonizing names for brothers and sisters in Christ who voted for Trump are in total contrast to the Lords command to love each. There’s no Christian excuse for nasty, bitter name calling. What happened to -they’ll know us by our love?

Why don’t you tell that to all the MAGA “Christians” who went after principled conservative Christians like David French and others who had the audacity to state that character matters?