Since 1988, 20 out of the 25 first-place men in the Boston Marathon have been Kenyan. Of the top 25 male record holders for the 3,000-meter steeplechase, 18 are Kenyan.

Eight of the 10 fastest marathon runners in history are Kenyan, and the two outliers are Ethiopian. The fastest marathon time ever recorded was Kenyan Eliud Kipchoge’s in the 2018 Berlin Marathon. The fastest women’s marathon ever recorded was Kenyan Bridgid Kosgei’s in the Chicago Marathon.

Three-quarters of these Kenyan champions come from the Kalenjin ethnic minority, which has only 6 million people, or 0.06% of the global population. The Kalenjin live in Kenya’s Rift Valley. Iten, a town that sits on the edge of the valley at 7,000 feet above sea level, is nicknamed the City of Champions.

“If you look at it statistically, it sort of becomes laughable,” said David Epstein, a former senior writer at Sports Illustrated. “There are 17 American men in history who have run under 2:10 in marathons. There were 32 Kalenjin who did it in October of 2011.”

American journalists have been fascinated by Kalenjin runners for decades, and their explanations for Kenyan dominance in running have included training, culture, biology and diet. However, one factor remains little explored or understood in media coverage: The spiritual lives of the Kalenjin runners have received scant attention.

Your tax-deductible gift helps our journalists report the truth and hold Christian leaders and organizations accountable. Give a gift of $30 or more to The Roys Report this month, and you will receive a copy of “Hurt and Healed by the Church” by Ryan George. To donate, click here.

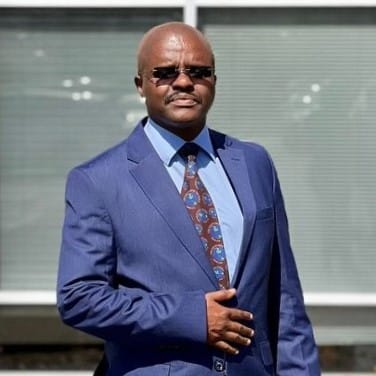

Lawrence Cherono, winner of the 2019 Boston and Chicago marathons, told ReligionUnplugged.com that journalists never ask him about his Christian faith. And when he brings it up in interviews, journalists quickly change the subject.

The vast majority of these runners were raised in either Protestant Christian or Roman Catholic households, and they frequently attribute their success to the discipline and support that their religious faith has given them.

John Njoroge Miaka, who won the Madrid Marathon in 2000 and the Valencia Marathon in 2001, said in an interview, “Kenya is not like Europe or America. Christianity holds us up. We expect miracles. Even runners who don’t go to church carry small Bibles around with them and read their Bibles for inspiration. They trust in the God of the Bible.”

Eliud Kipchoge, the only person in history to run a marathon in less than two hours, told Swiss journalist Jürg Wirz, “Religion plays a very important role in my life. It keeps me from doing things that could keep me from my goals. On Sundays, I go to church with my family, and I pray regularly, even in the mornings before a race.”

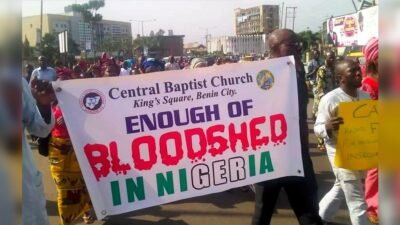

In October 2019, Tom Osanjo published an article in ReligionUnplugged.com about how churches throughout Kenya met on the day of the race to pray for Kipchoge’s success. “We are going to be Eliud’s pacemakers in prayer,” a parishioner told Osanjo.

Marathon runners are national heroes in Kenya, and their religious beliefs commit them to using their fame and wealth to serve their communities. Cherono said told me that from a very early age, he attended the Africa Inland Church. He was spiritually formed in a church that taught him to give back to society. Now that he has achieved fame, he is in the process of setting up the Lawrence Cherono Foundation to fund the digging of wells in his hometown, which lacks clean and abundant water.

Mary Keitany won the 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2018 New York City marathons. She and her husband, Charles Koech, have helped fund and build the Mary Keitany Shoe4Africa school in Mary’s hometown, Torokwonin, Baringo County. Mary had to drop out of school to become a housekeeper when she was a teenager. She wants to help other children in her hometown avoid a similar fate.

Wesley Korir won the 2012 Boston Marathon. He used his earnings to start a foundation that supports 2,000 farmers and pays for 300 children to go to school. Korir told the Guardian, “If I win a race, those kids go to school next year. If I don’t, they don’t. It is a very big motivation. When you reach the pain, you have a reason.” Korir is currently running for member of Parliament representing Rift Valley.

The Rev. David Nganga is the lead pastor of the Africa Inland Church Fellowship in Eldoret, Kenya. He has had several elite runners in his congregation. He recognizes them in worship services, and during races, his congregation prays for the runners.

His church produced Benjamin Limo, the only Kenyan athlete to win a gold medal in the Helsinki games. Nganga prayed for the entire Kenyan team at their training camp before they left for the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. Kenya won 13 medals — six gold, six silver and one bronze — in Rio de Janeiro, marking its most successful Olympic outcome in history.

Nganga said that Kenyan churches must become as deliberate about pastoral care after the games as they are before the games. Kenyan athletes who come home as winners face a myriad of immense challenges. In rural parts of Kenya, a rich person is expected to help not only his or her family and his friends but also anyone lacking money for food, medicine or rent. Successful runners are plagued by requests from needy people.

They are also expected to appear at political rallies, at events by business owners to inaugurate shops and at church fundraisers. Such pressures can drive Kenyan runners to hide themselves in training camps or to move to Nairobi, where they can live anonymously.

In the worst cases, athletes squander their money in irresponsible investments and wild living. Nganga asks them, “How do you handle huge sums of money made in a very short time? How do you handle the temptations of sudden fame and wealth?

“Some athletes have not responded well to these challenges, he said. “There have been suicides, divorce, separations, polygamy.”

Nganga said that churches are in a position to intervene to provide pastoral care, spiritual counseling, marital support and financial advice for returning athletes. The church has the moral authority among athletes to be of great service to them, and Nganga believes that he and his church needs to rise to this challenge.

This story was originally published by Religion Unplugged.

Robert Carle is a professor at The King’s College in Manhattan. Dr. Carle has contributed to The Wall Street Journal, The American Interest, Religion Unplugged, Newsday, Society, Human Rights Review, The Public Discourse, Academic Questions, and Reason. Carle is reporting from Eldoret, Kenya.

5 Responses

This was very inspiring and encouraging.

I love this:

“Kenya is not like Europe or America. Christianity holds us up. We expect miracles. Even runners who don’t go to church carry small Bibles around with them and read their Bibles for inspiration. They trust in the God of the Bible.”

.

.

i love this even more:

“Cherono said told me that from a very early age, he attended the Africa Inland Church. He was spiritually formed in a church that taught him to give back to society.”

——————

No church i’ve being a member of has taught that. instead, the explicit and implicit message is to give to the church.

Give more, do more, be more — it all stays in-house. it all goes into building up the business: salaries, technology, insurances, and beautification. And perks, gifts, and rewards for the pastor.

that is the mission.

really, it’s false advertising.

Thanks for this comment. You’ve said all I would want to say, and better than I would have.

I think that many of these runners do realize Christianity is not a talisman nor is there such a thing as work salvation! I hope that the ones who think that one can work to salvation among this group of runners come to the realization that they can’t!

Hitchcock’s Dictionary on Good works

….

‘Works are “good” only when, (1) they spring from the principle of love to God. The moral character of an act is determined by the moral principle that prompts it. Faith and love in the heart are the essential elements of all true obedience. Hence good works only spring from a believing heart, can only be wrought by one reconciled to God (Eph. 2:10; James 2:18:22). (2.) Good works have the glory of God as their object; and (3) they have the revealed will of God as their only rule (Deut. 12:32; Rev. 22:18, 19).

‘Good works are an expression of gratitude in the believer’s heart (John 14:15, 23; Gal. 5:6). They are the fruits of the Spirit (Titus 2:10-12), and thus spring from grace, which they illustrate and strengthen in the heart.

‘Good works of the most sincere believers are all imperfect, yet like their persons they are accepted through the mediation of Jesus Christ (Col. 3:17), and so are rewarded; they have no merit intrinsically, but are rewarded wholly of grace.’

Apparently at my age, I should have a secretary. ???? The quote is from the Easton Bible dictionary❗

You can find the whole topic below, which is in the public domain, since it was done no earlier than the 1890’s.

https://www.biblestudytools.com/dictionaries/eastons-bible-dictionary/works-good.html

It’s one of the resources that you can have when you use the –free– AND bible app on an Android device.????

This fascinating article highlights an often-overlooked aspect of the success of elite Kenyan runners: their Christian faith. It’s intriguing to see how, beyond training, culture, biology, and diet, faith plays a crucial role in their performance and motivation. The way these athletes integrate their faith into their daily and sporting lives is truly inspiring, especially in a world where sports and spirituality are not always seen as going hand in hand. It shows a deeper dimension of their commitment and discipline, which goes beyond mere personal glory seeking. This article offers a refreshing and necessary perspective on the importance of faith in high-level sports.